Midterm Review

You should be worried.

The Exam Itself

When you say “write a memo” in the question, do you want an actual memo, or can we use a block form IRAC with issue, rule, and analysis listed separately?

Should we write back the jurisdictional rules you give us in the fact pattern in our rule paragraphs (ex. in this jurisdiction, for there to be x, etc.)?

How would you like us to use the restatements in our responses? For instance in contracts we will paraphrase and extract the rule. Would you say to use the same application for torts?

Would you prefer we cite to cases in our answer when articulating a rule?

If we struggle to remember case names because there’s so many, so if we want to refer to them in our analysis, can we just refer to them with an indicator that we remember?

If we have to write on res ipsa on the exam, do you want us to mention it as res ipsa loquitor first and thereafter as res ipsa?

Are there other jurisdictional differences we should know besides common carriers and res ipsa?

Would a statute on the exam tell us if punitive damage awards are available?

Why is it important to understand our role if we are an Appellate court, trial court, or Supreme Court judge? How is the procedural posture going to shape our answer on the exam?

Can you explain the argument about credibility of witnesses (the children who claimed they did not do anything) in the Res Ipsa Loquitor hypothetical an how you would frame the argument?

Some of the cases have contradictory holdings. How do we use them on the exam? Do we use the one that is the latest holding, or can we use either to support our arguments? Basically which is the “law” to follow.

Should we bring up dissent opinions if they fit within our argument on the exam? For example, for compensatory damages, the courts were split regarding whether consciousness should be required for loss of enjoyment and whether loss of enjoyment is a separate category from pain and suffering. Or should we only stick to the rules held by the majority?

If we’re given one side to argue, should we bring in counterarguments? Or is it not necessary?

How do we incorporate libertarianism and utilitarianism schools of thought into our analyses?

Damages

Two separate legal inquiries:

- Liability

- Damages

[fit] Compensatory

[fit] Damages

and punitive damages

Compensatory Damages

The Objective: To restore the plaintiff to the state they were in before the harm caused by the defendant.

Questions

Does a jury always decide damages? Will we have to calculate damages for this exam?

With the McDougald v Garber case you were discussing deterrence and its relation to compensation and limits, but I don’t understand the relationship between the three concepts.

Punitive Damages

BMW v. Gore Guideposts

- Degree of reprehensibility

- Ratio of punitive damages to harm inflicted on plaintiff

- Comparison with civil or criminal penalties

State Farm Excess of single digit ratio is presumptively unconstitutional

—

Questions

When discussing punitive damages, we spoke about notice. What exactly does this mean? Are punitive damages only appropriate where a defendant was given prior warning to his conduct? Is it true that there has to be fair notice for tort liability? Or is this just a policy consideration since fair notice is considered in criminal laws?

For evaluating excessive punitive damages, under the degree of reprehensibility, one of the factors to consider is punishment for other actors. I was unable to find this specific terminology in the punitive damages cases. Is this connected to the State Farm case regarding intra-state punishment (only using out-of-state actions by the actor for determining reprehensibility but not for damages)?

With the three guideposts (from BMW) being only “standard like”/just considerations, why then is there a concern about encroaching on states’ rights?

Negligence

Negligence as a Cause of Action

Plaintiff must prove four elements:

- Duty

- Breach

- Causation

- Harm

Negligence as a Concept

Relates to the elements of duty and breach

The “fault” principle

Defined as a failure to exercise “reasonable care”

Proving negligence

Questions

To clarify, “negligent” does not mean “liable”? When we are analyzing breach - is the outcome just that the defendant has not exercised reasonable care or are we suggesting liability? Just want to confirm as I believe liability is not confirmed until we go through all the elements (including causation and harm).

If the plaintiff was negligent (per se or prima facie) does that entirely negate their negligence claim against the defendant? Or is it just something that it part of the larger facts to be assessed?

Is a prima facie case of negligence simply one where the 4 elements have to be proven to prove there is negligence?

If we make out a prima facie case of negligence (so all 4 elements met), does this mean it always goes to a jury to be ruled on liability and damages?

If we find that a defendant was negligent based on duty and breach, how would we conclude? “Thus, the defendant is negligent as a concept”?

On an exam if we are asked “was the defendant negligent as a concept?” Which only refers to duty and breach, would we first determine duty and then breach? Or would it be breach first then duty?

If negligence is found as a concept only but not as a matter of law, does that mean case dismissed?

Can we go over a bit more on how to frame our answers? Particularly for different ways to prove reasonable care.

—

How does a plaintiff normally prove duty and breach?

D was legally obligated to do X.

D failed to do X.

Therefore, D breached their legal duty.

—

Detailed version

D had a duty (to the plaintiff) to exercise reasonable care under the circumstances. Reasonable care under the circumstances was X, because of

- foreseeability,

- reasonable person standard,

- custom,

- statute,

- or hand formula.

D failed to do X.

Therefore D acted negligently / breached their legal duty to plaintiff.

—

Reasonable Person Standard

Objective standard

Exceptions to objective standard:

- Physical disability

- Children

- Expertise

Not exceptions to objective standard

- Mental disability

- Children engaged in adult activity

- Old age & infirmity

—

Questions

To clarify on Rst 3rd §§ 10 and 283, a child over 5 can be negligent?

The use of “reasonable” in both the general reasonable care under the circumstances duty and the Reasonable Person Standard has me a bit confused. As I understand it, reasonable care is the defined duty and the reasonable person standard is what you use to define a person’s actions to give life to whether they did or did not breach that duty.

On the midterm, if we are given a question that requires us to describe a “reasonable person” do we make up a story about what we think a reasonable person would do in that circumstance?

—

Foreseeability

Foreseeability is a flexible concept.

Define any event in general enough terms and it is foreseeable.

Define any event in narrow enough terms and it is unforeseeable.

How to use customs and statutes

Sword for proving negligence Prove two things:

- Custom or statute = reasonable care

- Defendant failed to comply with custom or statute

-—————————————————

Shield for disproving negligence

Prove two things:

- Custom or statute = reasonable care

- Defendant complied with custom or statute

Negligence per se

- Actor violates a statute that is designed to protect against this type of accident and harm

AND

- the accident victim is within the class of persons the statute is designed to protect.

Questions

I know negligence per se is about the statutory violation, but does this automatically make negligence per se qualify as negligence as a matter of law as well?

Is there a true line between a statute that is a “safeguard to preserve life/limb” and a statute that is “organizing human behavior”? (re: Tedla)

In class, we discussed factors like: “Absurd results,” Whether the statute is “really about safety,” “Exceptions or unusual circumstances.” How should we use these as “red flags?” Like procedurally when would we view these as issues? Do these apply when determining the “class of persons” protected by a statute, or do they remain relevant even after establishing that an individual falls within that class?

In The T.J. Hooper, Hand explains that just because a custom is a certain way does not mean that one did not act reasonably under the circumstances. Is this case decided to provide a standard for society? One could just as easily say “yeah nobody else was putting up radios so it’s not reasonable under the circumstances to have expected that.”

Statutes are one way to help prove what reasonable care under the circumstances would be, but in the case we studied (w/ the shower door) the court did not allow them to bring in the statute as it was not applicable law. I thought I remember learning we can use statutes to help prove custom, but if the court did not allow it in this case, how should we use statutes to prove custom?

With Trimarco. while discussed under customs and statutes, it seems more about judge/jury dynamics. If I understand correctly, the issue was whether General Business Codes could be introduced as evidence to prove “custom,” and the appellate court ruled against it, fearing it would mislead the jury. How does this fit into the broader analysis?

Hand Formula (BPL)

B = Burden of precautionary measures

P = Probability of loss/harm

L = Magnitude of loss/harm

IF B < PL

AND defendant did not take on B

THEN defendant was negligent

IF B > PL

AND defendant did not take on B

THEN defendant was NOT negligent

Questions: Hand Formula

Can you also go over the hand formula again?

Can you explain why probability of loss/harm is difficult to determine?

Questions: Role of Judge & Jury

Can duty only be established by the judge?

Can breach only be a question for a jury?

Does Goodman or Pokora apply? Doesn’t Akins also counter Pokora since there’s no jury determination for standard of care like in Goodman? How/When do we apply these cases?

In Akins (the ballpark injury case), the appellate court overturned the trial court’s decision, which had held that reasonable care under the circumstances should be a jury question. The appellate dissent agreed with the trial court. Does this mean the appellate court can decide matters of law as they see fit? What justified the appellate court’s determination? There doesn’t seem to be a strict legal basis beyond their authority. Was it to prevent absurd results or based on policy considerations?

I feel that there are always arguments for why a case should go to a jury or why something should be decided as a matter of law. How do we reconcile that? Is it like what you said, “come to a conclusion and work backwards?”

Res ipsa requirements:

- Harm results from the kind of situation in which negligence can be inferred

- Defendant was responsible for the instrument of harm

—

Questions: Res Ipsa

Can you please go over res ipsa again with an example, I’m confused on the first element?

Can you go over the difference between res ipsa and negligence per se?

What distinguishes St Francis and Nicollet Hotels?

How does Connolly apply to Res Ipsa? In reviewing this case – most of my brief and notes from class are doing just that: establishing what the defendant ought to have done to control its guests to protect pedestrians. I feel myself slipping away from Res Ipsa to instead establish a standard of care. When we start evaluating the facts to see if they indicate foreseeability/reasonable care, why are we not outside of Res Ipsa land?

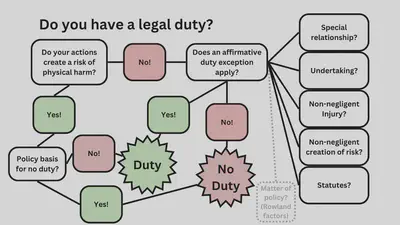

Connolly v. Nicollet Hotel, would you be willing to run through the duty flow chart with this case?

Existence of Duty

—

Rowland Factors

- foreseeability of harm

- certainty of plaintiff’s injury

- connection between defendant’s conduct and plaintiff’s injury

- moral blame

- policy of preventing harm

- burden to defendant

- consequences to community

- availability of insurance

If a set of facts indicates no action causing a risk of physical harm, we then assess whether an affirmative duty exception applies?

When doing the duty chart on an exam, if you answer yes to “If defendant created a risk of physical harm?” Would you also consider whether there would be an affirmative duty even if you answered yes, just in case? Or is it just a judgment call if it’s a grey area?

Do we have to go through all possibilities, for example if we answer “no” to the creation of risk question on the flow chart and go one way, should we also answer the “yes” and go the other? (making arguments for each side)

For duty, if we are determining it, and the action does create a risk of physical harm, can we just say like “Yes, this action creates a risk of physical harm” then determine it? Once we establish an affirmative duty, how do we assess a breach? Do we use the same framework—foreseeability, the reasonable person standard, custom, and statute—to determine what was reasonable under the circumstances?

I was reviewing the material on “Duty” and realized I’m a bit confused about what triggers the “created the risk of physical harm” factor in determining whether a defendant has a legal duty. I think I may be interpreting it too much like a but-for cause. For example, in a situation where the defendant failed to act—such as in your example from class on Friday, where the rock climbing instructor noticed the rope wasn’t tied correctly but did nothing—I initially thought this would create a legal duty because, had the instructor fixed the rope, the injury would not have occurred. From my understanding, this is not the correct way to analyze the “creation of the risk” factor. Could you clarify what type of action actually constitutes creating the risk?

How do you analyze a situation where one person owes mutually exclusive duties to two different people? In my head, I’m imagining a driver with a passenger and a pedestrian. Under some extreme situation, there is a scenario where the driver has to choose between injuring the passenger or the pedestrian. Whatever decision is made, for the duty that was breached, can you use the fact there was a mutually exclusive duty pulling in the opposite direction for the Reasonable Person Standard or would it be irrelevant since we’re interested in the relationship between the driver and the person who actually got hurt?

Joint venture- I have in my notes it can be both an undertaking and a special relationship, is it true?

Why was Harper not a special relationship through companionship on a social venture like Farwell?

For an undertaking analysis where we are meant to find whether there is a duty or not, do you use reasonable care to define whether a duty exists? I’m thinking about a situation where Person A helps Person B after B suffered a severe injury (say broken arm and leg). Person A comes over and puts B’s arm in a sling, but then just leaves them.

What is the distinction, if any, between the affirmative duty statute exception and negligence per se? Is a breach of an affirmative duty created by a statute considered negligence per se?

If a father and son are engaged in an adult activity (say hunting and the son is 8 years old), there would then be a joint venture duty under the special relationship exception?

Is this a correct understanding of joint venture? A group of hikers would have an obligation to each other. If Garvin injures himself, and Susie helps him, duty kicks in when she starts to help. If she stops helping to check on her cats on her home camera, she has breached that duty under undertaking. If John walks away and says “Good luck, Garv!”, he has breached that duty under special relationship via joint venture.

I have a question regarding the Savonia driving hypo. I’m having trouble understanding what actions we are supposed to analyze for the first step of the chart.

When evaluating whether a defendant’s actions created a risk of physical harm, what is a scenario in which an affirmative duty exception applies? (I am specifically confused on the hypothetical where Savonia is driving and accidentally hits someone because we analyzed affirmative duty exceptions, but I thought driving was considered an action that created a risk of physical harm. If that is the case wouldn’t Savonia have a legal duty regardless because she satisfied the first requirement of determining a legal duty?)

Could you please go over the difference between the initial creation of risk of harm and the non-negligent creation of risk of harm? I’ve been trying to work through the banana stand example. I see how the driver’s inaction doesn’t initially create a risk of harm (the harm already existed), but I’m confused about when the affirmative duty kicks in. Does she have that duty because she caused the initial risk by hitting the stand (albeit non-negligently)?

For Non-negligent injury, do we apply both the classic and modern rule, or just go off the modern rule?

Can you explain the difference between the non-negligent injury vs. non-negligent creation of risk?

Can you explain another example (besides the banana stand) of Non-Negligent Injury, and Non negligent creation of risk ? I am having trouble differing between both. Also do they both work together?

Is this a correct understanding of non-negligent creation of injury? Nailah’s brakes give out and drives into a cocoa tea stand knocking down all the cocoa tea, Kes walks by and slips on the spilled cocoa tea, injuring his hip. Nailah has a duty to mitigate further injury to Kes, but she’s on Instagram Live instead of calling for help.

Is this a correct understanding of non-negligent creation of risk? Nailah’s brakes give out and drives into a cocoa tea stand knocking down all the cocoa tea, Kes walks by and slips on the spilled cocoa tea, injuring his hip. Nailah had a duty to mop up the cocoa tea when she spilled it before Kes walked by, mitigatingthe pre-existing risk of Kes slipping and falling.

What is the common law understanding of special relationship? And why wouldn’t it apply to tarasoff

When thinking of whether (or not) there is an affirmative legal duty of a third party in the absence of a specific carveout of the affirmative duty exceptions, like in the hypothetical do we apply the Rowland factors as their own separate test/analysis? Do we apply Rowland on its own or do we consider Rowland with one of the other affirmative duties?

What’s the importance of the Rowland factors? Can you give more examples? Do the Rowland factors only apply to medical professionals and the duty they owe to third parties? Or can we always discuss them when harm befalls a 3rd party? If we had a question that is similar to Randi the predatory case, to find liability on the school, and if the rowland factors didn’t apply, could you argue special relationship (because it is a kid, and a teacher and the teachers as administrators have responsibility to take care of kids) ?

Can you give specific examples of how Rowland factors are used to determine a policy basis for courts to assign duty? How heavily do they weigh? (Like in the optometrist example)? Could we go over the optometrist example again? I am a little confused on it and want some clarity on specifying what the duty is - especially the action: is the duty to exercise reasonable care to warn the patient about driving?

Policy Basis for No Duty

Was there no duty in Reynolds for 3rd parties because its not fair to extend commercial host standards on social or hosts, or was there no duty because the statute was not meant to protect third parties?

When discussing courts finding no duty on policy grounds, we said “Courts properly do this, according to the Third Restatement, when they articulate ‘categorical, bright-line rules of law applicable to a general class of cases.’” How do we know if a matter is included in the “bright line rule”? I remember discussing crushing liability for private companies providing quasi-public functions. Are there any more we need to know?

When determining whether a consideration of public policy exists to impose a legal duty, how do we come up with that decision? Is that a matter of just coming up with it on our own? Because, with statutes, the law will determine whether you had a duty or not. So, what I’m trying to get at is, how do we know whether a public policy exists or not?

Duties of Landowners and Occupiers

—

Traditional View

| Type of Visitor | Definition |

|---|---|

| Trespasser | Intruder |

| Licensee | Social guest |

| Invitee | Business guest or general public (if land opened to public) |

Duties Owed — Traditional View

Trespasser

- duty not to intentionally or wantonly cause injury

- no duty of reasonable care (with handful of exceptions)

Licensee

- no duty to inspect or discover dangerous conditions

- duty to warn or make known conditions safe

Invitee

- duty to inspect and discover dangerous conditions

- duty to warn or make conditions safe

Modern View

| Type of Visitor | Definition |

|---|---|

| Trespasser | Intruder |

| Everybody else | Not a trespasser |

Duties Owed — Modern View

Trespasser1

- duty not to intentionally or wantonly cause injury

- no duty of reasonable care (with handful of exceptions)

Everybody Else

- duty of reasonable care

—

Questions: Duty of Landowners and Occupiers

Should we use both traditional and modern when talking about duty to landowners/occupiers, or will you specify which to use in the test?

At what point does something switch from a Licensee to Invitee? Like if it’s a private party (invite only) but there’s a few hundred attendees, would that still count under social guest or would that veer into open to the general public?

For duty of landowners, if the trespasser is a child, is there always a duty of reasonable care?

Is the duty imposed on landowners and possessors a completely different flow chart than the creation of risk that we have talked about?

For duty of landowners, can you clarify what a “duty to not intentionally or wantonly injure” means for adult trespassers? Would this example be considered intentionally injuring a trespasser. (EX: landowner sets hidden traps on land with the intention to keep out unwanted visitors and animals; Adult trespasser accidentally steps onto the trap and gets seriously injured)

It’s clear that permission from the possessor can turn a trespasser into a licensee/invitee, but does revoking permission turn them into a trespasser? If so, how does that work?

Or in California and the Third Restatement, a “flagrant” trespasser rather than just a plain old trespasser ↩︎